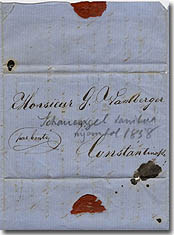

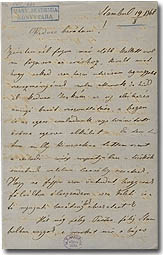

In March 1857, when Vámbéry left his country for the

first time, he also opened a new chapter in his life, as the period of private tutorship, practised since his student age, came to an end – at least in his

homeland. The idea of traveling to the East was matured by him under the influence of

his readings, and his modest savings gave him hope to a change. His journey to

Constantinople, which has become a reality thanks to the support of his patrons,

primarily of József Eötvös, who recognized his talent,  1

offered an outbreak from his situation. The unparalleled amount of knowledge,

absorbed from the books he read in a dozen of languages, provided with a

considerable theoretical framework the young man driven by curiosity, who

now had the opportunity to study a foreign culture in its real context. The

Turkish language, which he could not practise at home, now surrounded him as a

living language.

1

offered an outbreak from his situation. The unparalleled amount of knowledge,

absorbed from the books he read in a dozen of languages, provided with a

considerable theoretical framework the young man driven by curiosity, who

now had the opportunity to study a foreign culture in its real context. The

Turkish language, which he could not practise at home, now surrounded him as a

living language.

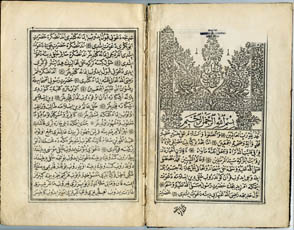

Vámbéry

set out by ship along the Danube, and arrived through the port city of Galați

and the Black Sea in the Ottoman capital. His talent of languages attracted the

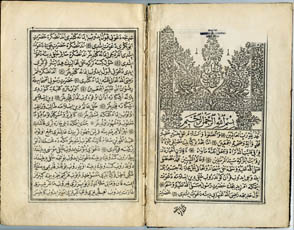

attention of his fellow travelers already on the way: on one occasion he won the

confidence of a Muslim traveler by reading aloud a portion of the religious

handbook Kirk Sual (Forty Questions).

Vámbéry

set out by ship along the Danube, and arrived through the port city of Galați

and the Black Sea in the Ottoman capital. His talent of languages attracted the

attention of his fellow travelers already on the way: on one occasion he won the

confidence of a Muslim traveler by reading aloud a portion of the religious

handbook Kirk Sual (Forty Questions).  However,

the unpredictability and uncertainty of day-to-day existence followed him since

the moment he landed in the Galata neighborhood of Istanbul. As he wrote in his

memoirs: “I had no idea where I would stay and, completely penniless, how

I would

make my living in this strange city.”

2

However,

the unpredictability and uncertainty of day-to-day existence followed him since

the moment he landed in the Galata neighborhood of Istanbul. As he wrote in his

memoirs: “I had no idea where I would stay and, completely penniless, how

I would

make my living in this strange city.”

2

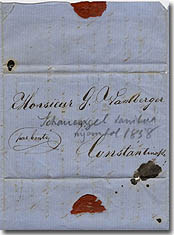

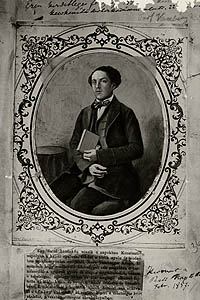

He owed a lot to the Hungarian emigrants, who were informed about his journey

from the Hungarian newspapers. Among the several Hungarians in Istanbul, he

first met a certain “Mr. Püspöky”

3 immediately after his landing in the city, who also helped to

resolve his problem of accommodation. Vámbéry also mentions the names of

several Hungarian emigrants as his supporters, including István

Türr (1825-1908), Sándor Veress, Balázs Orbán (1829-1890) and Lajos Splényi (1817-1860).

4 His most important Hungarian connection was probably his friendship with Dániel Szilágyi. In the years after the Crimean war, this former hussar officer,

who emigrated to Constantinople in 1849, operated an antiquarian bookshop,

where he passionately collected Turkish books and manuscripts.

Although there is no clear evidence, it is assumed that Vámbéry seized a part

of his Oriental manuscripts through the mediation of Szilágyi. When this latter

died in 1885, Vámbéry called the attention of the Hungarian Academy to his

legacy of unparalleled value, and his manuscripts were purchased in 1886 with

Vámbéry’s cooperation.

where he passionately collected Turkish books and manuscripts.

Although there is no clear evidence, it is assumed that Vámbéry seized a part

of his Oriental manuscripts through the mediation of Szilágyi. When this latter

died in 1885, Vámbéry called the attention of the Hungarian Academy to his

legacy of unparalleled value, and his manuscripts were purchased in 1886 with

Vámbéry’s cooperation.

His relationships developed with the members of the Ottoman political elite were

even more important than his good relations with the Hungarians living in

Istanbul. His interest in everyday language and behavior, his quick

comprehension and literary erudition helped him to win the confidence of the

Turks, and to develop relationships leading to the highest circles of the

Ottoman political elite. In his memoirs he remembers like this: “The more I got

acquainted with this new moral system and the deeper I penetrated into the ways of

living and thinking of Oriental people,

the larger the circle of my acquaintances became, and the easier the doors opened before me, not only in the houses of the simple officers, but also in

those of the high and highest dignitaries.”

the larger the circle of my acquaintances became, and the easier the doors opened before me, not only in the houses of the simple officers, but also in

those of the high and highest dignitaries.”

The possibility of rapid social success had a liberating effect on him, because

unlike in his country, “in Turkey the born aristocracy is unknown”.

5

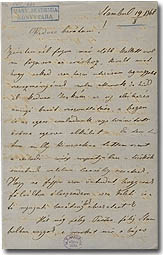

As he wrote in a letter to József Budenz at the beginning of his second journey,

on 19 August 1861: “I did not know how great treasures I gained in the troop of

the real مؤمنين

6

: the Turks love me, really, intrinsically love me.”

7

Vámbéry wanted to earn his living also in Turkey by his previously gained

science and kowledge of languages. Thanks to his ever extending system of

Turkish relationships,

and also to the support of the Hungarian émigré officer György Kmetty (in his

Turkish name, Ismail Pasha) he received a teacher’s position in the house of

Husein Daim Pasha. From the Pera neighborhood, which was mainly inhabited by

Europeans, he moved to the Turkish-populated Katabaş. There he was given the

name Reshid (“well-led, the one going on the right path), which he from then on

used in the Muslim world. The process of “becoming Turk” was a noticeably

exciting challenge for him, but his metamorphosis remained always an outward

one. He writes about it like this:

“The Turkish disguise put on myself, as well as my

pretended Oriental personality and knowledge were merely outward appearances,

because not only was my soul deeply permeated by the Western spirit, but the

deeper I penetrated into the life and way of thinking of the Asian society, the

more passionate my devotion to the West became, because it became clear to me,

that the human existence worthy of this name and all that is really noble and

sublime, can find its way only in the framework of the aspirations of the West.”

8

His ability to learn and his adaptability were acknowledged by the

fact that he was considered a muhtedi, a real convert who was led on the

path of the truth. However, he writes:

“the idea of conversion could not put roots in my mind,

because although I had been permeated for a long time by the ideals of the absolute

freethinkers, in the Islam I found a system of beliefs which, due to its solid

foundation and rational dogmas, was the more dangerous for the free flight of the

spirit, and due to my open hostility to every positive religion, was the more

damnable in my eyes.”

9

“the idea of conversion could not put roots in my mind,

because although I had been permeated for a long time by the ideals of the absolute

freethinkers, in the Islam I found a system of beliefs which, due to its solid

foundation and rational dogmas, was the more dangerous for the free flight of the

spirit, and due to my open hostility to every positive religion, was the more

damnable in my eyes.”

9

In 1859, two years after his arrival in Istanbul he taught history, geography

and French language in the house of the recently deceased renowned statesman and

former foreign minister Sadik Rifat Pasha

(1801-1857), to his son Rauf. There he was absorbed in Turkish social life: as a

guest of social gatherings and receptions, he had the opportunity to develop

relationships with the members of Turkish literary societies and political

elite. He became a frequent guest in the upper echelons of the political elite,

where he got in contact with the most influential personalities of the Ottoman

reform era (Tanzimat), Fuad Kechijizade Pasha (1814-1868), Mehmed Emin Ali Pasha (1815-1871),

Mustafa Reshid Pasha,

as well as with the later intellectual father of the Turkish constitution,

Midhat Pasha (1822-1884). He also mentions his relations with some important

statesmen, Rushdi Mehmed Pasha(1811-1882) or Kibrisli Mehmed Emin Pasha (1813-1871),

and he also gave lessons in the house of Mahmud Nedim Pasha

(1818-1883), a representative of the pro-Russian political aspirations. He could also

meet the great intellectual figures of the Turkish reforms, including the

renowned author Ibrahim Shinasi

(1826-1871), the founder of the Istanbul journal Tasvir-i Efkar (1862).

On the recommendation of Kibrisli Mehmed Pasha, on one occasion he was also the

interpreter of Sultan Abdulmedjid (1839-1861).

as well as with the later intellectual father of the Turkish constitution,

Midhat Pasha (1822-1884). He also mentions his relations with some important

statesmen, Rushdi Mehmed Pasha(1811-1882) or Kibrisli Mehmed Emin Pasha (1813-1871),

and he also gave lessons in the house of Mahmud Nedim Pasha

(1818-1883), a representative of the pro-Russian political aspirations. He could also

meet the great intellectual figures of the Turkish reforms, including the

renowned author Ibrahim Shinasi

(1826-1871), the founder of the Istanbul journal Tasvir-i Efkar (1862).

On the recommendation of Kibrisli Mehmed Pasha, on one occasion he was also the

interpreter of Sultan Abdulmedjid (1839-1861).

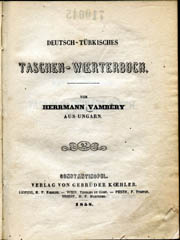

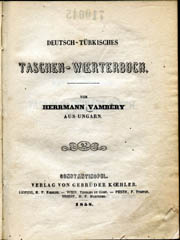

His

Istanbul period was also an important milestone of his scholarly career. He

visited libraries, where he focused on the Turkish historical works, and

especially on their parts referring to Hungary. At that time he published his

first work of his own, a German-Turkish pocket dictionary. His literary

ambitions are illustrated by his more than twenty essays published until 1861 in

Hungarian journals and magazines. Among others, he published the translations of

the Hungarian-related chapters from the historical works of Ibrahim Pechevi (1572-1650)

and Hodja Mehmed Sadeddin (1536/37-1599) in the Vasárnapi Ujság, the Új

Magyar Múzeum, and the Hazánk. He also translated some parts from Ahmed Feridun’s (died 1583)

collection of historical documents, published in print in 1858, for the Magyar Történelmi Tár,

and later for Az Ország

Tükre. He also wrote a large number of linguistic articles, reports and

popularizing essays, mainly for the Vasárnapi Ujság and the Pesti Napló.

An important scientific event of his Istanbul period was, that in 1860 he

discovered the only known copy of the 16th-century Turkish-language Hungarian

chronicle Tarih-i Üngürüs, which he donated to the Academy.

His

Istanbul period was also an important milestone of his scholarly career. He

visited libraries, where he focused on the Turkish historical works, and

especially on their parts referring to Hungary. At that time he published his

first work of his own, a German-Turkish pocket dictionary. His literary

ambitions are illustrated by his more than twenty essays published until 1861 in

Hungarian journals and magazines. Among others, he published the translations of

the Hungarian-related chapters from the historical works of Ibrahim Pechevi (1572-1650)

and Hodja Mehmed Sadeddin (1536/37-1599) in the Vasárnapi Ujság, the Új

Magyar Múzeum, and the Hazánk. He also translated some parts from Ahmed Feridun’s (died 1583)

collection of historical documents, published in print in 1858, for the Magyar Történelmi Tár,

and later for Az Ország

Tükre. He also wrote a large number of linguistic articles, reports and

popularizing essays, mainly for the Vasárnapi Ujság and the Pesti Napló.

An important scientific event of his Istanbul period was, that in 1860 he

discovered the only known copy of the 16th-century Turkish-language Hungarian

chronicle Tarih-i Üngürüs, which he donated to the Academy.

His further career was determined by his Istanbul experiences, especially by his

interest in the Eastern Turkic languages and in the works necessary to study

them. In this period he had the occasion to read some Eastern Turkic works in

the library of Ali Pasha.

Through his acquaintances he had a better overview of the Turkish political

processes of outstanding importance for the European public opinion, and thus he

became an appreciated occasional Istanbul correspondent for various journals,

such as the Augsburger Allgemeine Zeitung or the Viennese Wanderer.

His reports published in the Hungarian journals are also good evidences for his

unfolding publicist’s and journalist’s activity.

His Istanbul study years created for him the opportunity to step further. He

felt that his translator’s and interpreter’s work earned him not only a good

living, but also enough fame and honor to continue his career

as a high-rank Ottoman officer. Nevertheless, he voluntarily resigned it, due to

his adventurous nature which always sought new challenges. The reasons why he

did not establish himself in Istanbul, were presented in his confessions: “…

I myself do not know why, but I was not attracted by a Turkish bureaucratic

career, and by the perspective of being the employee of a state which is only

barely tolerated in Europe.” At the same time “… I would have probably soon had

enough of even the greatest success in this field, first because my rampant

feeling of freedom would have not tolerated for long any kind of subordination,

and second because I was and have remained an incorrigible enthusiast and

dreamer, and I only found enjoyment in extraordinary things.”

10

as a high-rank Ottoman officer. Nevertheless, he voluntarily resigned it, due to

his adventurous nature which always sought new challenges. The reasons why he

did not establish himself in Istanbul, were presented in his confessions: “…

I myself do not know why, but I was not attracted by a Turkish bureaucratic

career, and by the perspective of being the employee of a state which is only

barely tolerated in Europe.” At the same time “… I would have probably soon had

enough of even the greatest success in this field, first because my rampant

feeling of freedom would have not tolerated for long any kind of subordination,

and second because I was and have remained an incorrigible enthusiast and

dreamer, and I only found enjoyment in extraordinary things.”

10

His work was rewarded with an important recognition in his homeland: in the

spring of 1861 Vámbéry was elected a corresponding member of the Academy. After

four years of absence he returned to Pest with the strong determination of an

Eastern study trip. He held his inaugural speech in April 1861 in the topic of

Ottoman chronicles, and then he turned to the President of the Academy, Count

Emil Dessewffy (1814-1866) for a support to his planed Central Asian journey.

Constantinople – Stambool. Map

of J. R. Davies from

1860, the period of Ármin Vámbéry’s stay in the city (full

map here, 8 MB)

1

offered an outbreak from his situation. The unparalleled amount of knowledge,

absorbed from the books he read in a dozen of languages, provided with a

considerable theoretical framework the young man driven by curiosity, who

now had the opportunity to study a foreign culture in its real context. The

Turkish language, which he could not practise at home, now surrounded him as a

living language.

1

offered an outbreak from his situation. The unparalleled amount of knowledge,

absorbed from the books he read in a dozen of languages, provided with a

considerable theoretical framework the young man driven by curiosity, who

now had the opportunity to study a foreign culture in its real context. The

Turkish language, which he could not practise at home, now surrounded him as a

living language. Vámbéry

set out by ship along the Danube, and arrived through the port city of Galați

and the Black Sea in the Ottoman capital. His talent of languages attracted the

attention of his fellow travelers already on the way: on one occasion he won the

confidence of a Muslim traveler by reading aloud a portion of the religious

handbook Kirk Sual (Forty Questions).

Vámbéry

set out by ship along the Danube, and arrived through the port city of Galați

and the Black Sea in the Ottoman capital. His talent of languages attracted the

attention of his fellow travelers already on the way: on one occasion he won the

confidence of a Muslim traveler by reading aloud a portion of the religious

handbook Kirk Sual (Forty Questions).  However,

the unpredictability and uncertainty of day-to-day existence followed him since

the moment he landed in the Galata neighborhood of Istanbul. As he wrote in his

memoirs: “I had no idea where I would stay and, completely penniless, how

I would

make my living in this strange city.”

2

However,

the unpredictability and uncertainty of day-to-day existence followed him since

the moment he landed in the Galata neighborhood of Istanbul. As he wrote in his

memoirs: “I had no idea where I would stay and, completely penniless, how

I would

make my living in this strange city.”

2

where he passionately collected Turkish books and manuscripts.

Although there is no clear evidence, it is assumed that Vámbéry seized a part

of his Oriental manuscripts through the mediation of Szilágyi. When this latter

died in 1885, Vámbéry called the attention of the Hungarian Academy to his

legacy of unparalleled value, and his manuscripts were purchased in 1886 with

Vámbéry’s cooperation.

where he passionately collected Turkish books and manuscripts.

Although there is no clear evidence, it is assumed that Vámbéry seized a part

of his Oriental manuscripts through the mediation of Szilágyi. When this latter

died in 1885, Vámbéry called the attention of the Hungarian Academy to his

legacy of unparalleled value, and his manuscripts were purchased in 1886 with

Vámbéry’s cooperation. the larger the circle of my acquaintances became, and the easier the doors opened before me, not only in the houses of the simple officers, but also in

those of the high and highest dignitaries.”

the larger the circle of my acquaintances became, and the easier the doors opened before me, not only in the houses of the simple officers, but also in

those of the high and highest dignitaries.”