Gábor

Fodor:

Gábor

Fodor:

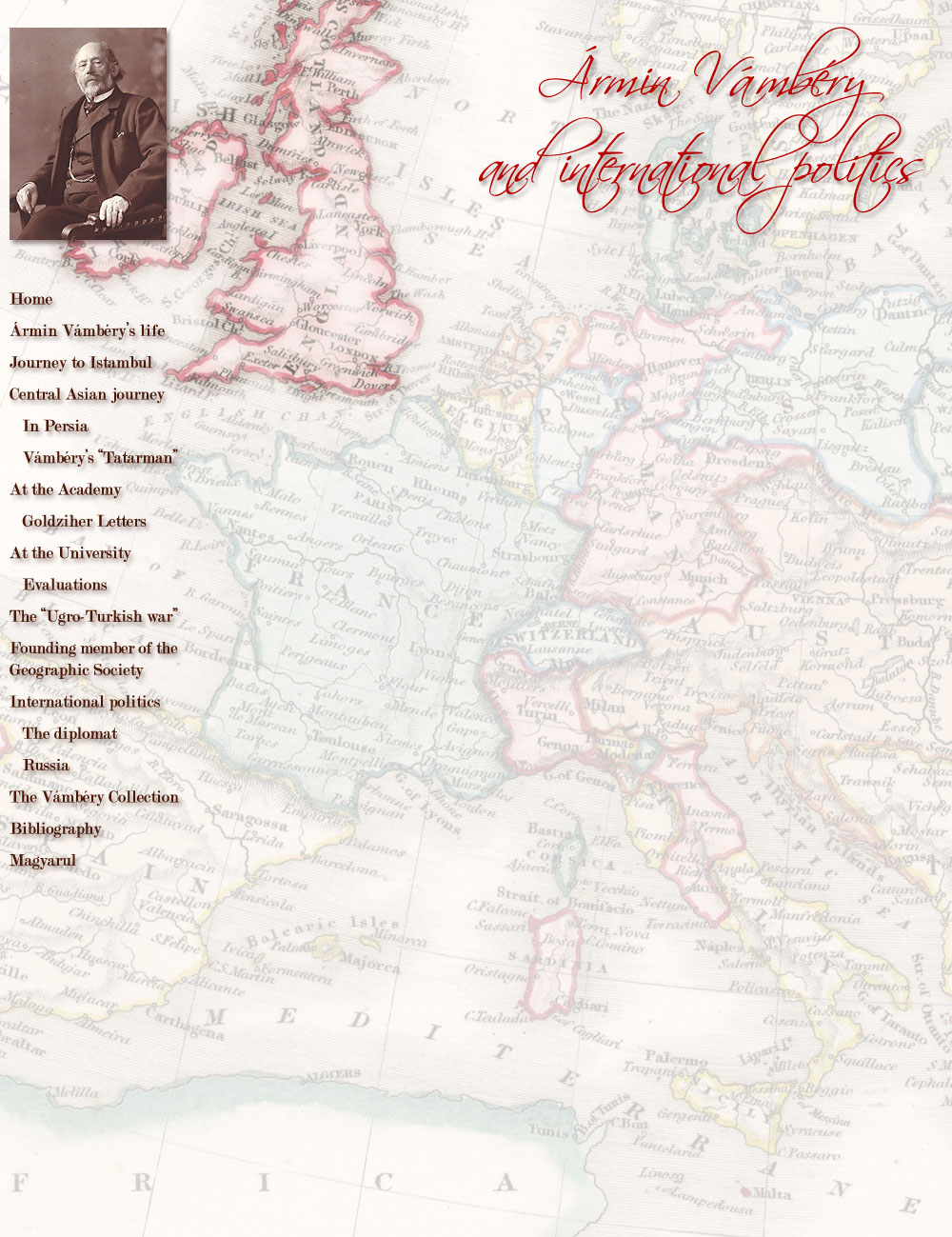

Vámbéry, the journalist, diplomat and mediator

Ármin Vámbéry first entered the land of the Ottoman Empire in 1857,

almost as a beggar. The young man encountering the colorful bustle of Istanbul

was immediately charmed by the atmosphere of the Eastern capital, so it is no

wonder that he devoted a large part of his life to the research of the Turks.

Vámbéry, who first earned his living from reciting Muslim holy texts, in a few

years became the home tutor and beloved guest of the families of the Ottoman

elite, so his name became known both to the European ambassadors accredited to

Istanbul,

and to the bureaucrats governing the domestic and international

politics of the Ottoman Empire. Moreover, the young man teaching foreign

languages had the occasion to personally meet Sultan Abdulaziz, and make

acquaintance with the young successor to the throne, Adulhamid II as well.

and to the bureaucrats governing the domestic and international

politics of the Ottoman Empire. Moreover, the young man teaching foreign

languages had the occasion to personally meet Sultan Abdulaziz, and make

acquaintance with the young successor to the throne, Adulhamid II as well.

The sympathy of the Turks, usually suspicious of Western people,

was won by Vámbéry through his excellent gift of languages, and through the

knowledge of Eastern habits (among others, by always bringing gifts with himself to

his visits), so he enjoyed a great esteem before the important officers of the Porta.

His fame was further increased by his Central Asian journey, started in

1861, after which half of Europe got to know him, and in Britain he was received

with honors due to a hero. The Hungarian explorer, who made a worldwide fame by

describing lands which were previously considered white spots, soon became

a popular guest of several members of the British royal family, and of a number

of influential aristocrats.

Appointed a teacher at the University of Pest, Vámbéry played an increasingly

important role in the development of the Anglo-Turkish and Hapbsburg-Turkish

relations, thus he was also received in the Ottoman court as a guest of honor.

This was especially so after the ascension to the throne of Sultan Abdulhamid II

(1876) and the Egyptian conflict (1882), as the new Ottoman ruler expected

Vámbéry, publishing worldwide and familiar with the Eastern mentality, to be the

messenger of the position of the Porta as well as its European contact.

Appointed a teacher at the University of Pest, Vámbéry played an increasingly

important role in the development of the Anglo-Turkish and Hapbsburg-Turkish

relations, thus he was also received in the Ottoman court as a guest of honor.

This was especially so after the ascension to the throne of Sultan Abdulhamid II

(1876) and the Egyptian conflict (1882), as the new Ottoman ruler expected

Vámbéry, publishing worldwide and familiar with the Eastern mentality, to be the

messenger of the position of the Porta as well as its European contact.

Known to the Turks as “Reshid efendi”, Ármin Vámbéry was considered

for three decades a special guest in the Dolmabahçe palace, but over the

years he became more and more estranged from his former friend, the wily, but

dictatorial Abdulhamid II. While in the late 1880s and early 1890 the Hungarian

scholar was received at the railway station of Istanbul by the Sultan’s orchestra,

and the Sultan’s aide personally cared for his comfort, and then Abdulhamid II

received him at private audiences (which was absolutely unusual from the Ottoman

ruler), their relationship increasingly deteriorated after the massacres of the

Armenian pogroms in 1894-1896. Although from 1889 Vámbéry stood in close

relationship with the staff of the British Foreign Office, and he regularly

reported about the conversations between him and the Sultan, this was not the

reason of the decrease of his role and the estrangement of his Turkish

relations.

The notorious anti-Russian researcher, who in 1849 personally lived through the

invasion of the Russian troops in Hungary, worked in all his life for a European

joining of forces against the empire of the Tsar, but after a time his efforts

interfered with great political interests. Thus, by the end of the first decade

of 1900 his

diplomatic and intelligence work became increasingly burdensome both to the

Brits in search of the friendship of Russia, and to the Hapsburgs at odds with

the Turks for the control over Bosnia, thus the aging scholar was put offline.

Until his death in 1913, Vámbéry could not influence any more his Western friends

as much as he did in the previous decades.

1

The notorious anti-Russian researcher, who in 1849 personally lived through the

invasion of the Russian troops in Hungary, worked in all his life for a European

joining of forces against the empire of the Tsar, but after a time his efforts

interfered with great political interests. Thus, by the end of the first decade

of 1900 his

diplomatic and intelligence work became increasingly burdensome both to the

Brits in search of the friendship of Russia, and to the Hapsburgs at odds with

the Turks for the control over Bosnia, thus the aging scholar was put offline.

Until his death in 1913, Vámbéry could not influence any more his Western friends

as much as he did in the previous decades.

1

The name of Vámbéry was soon forgotten in Turkey, entangled in war for almost a decade after the outbreak of WWI. The Hungarian scholar, who first told to Sultan Abdulhamid II about the existence of the Eastern branch of the Turks – and who also had his share in the wake and development of the Turkish national identity – came again in the spotlight in the early 1980s, but this time as a British secret agent. Mim Kemal Öke’s Abdulhamid II and his age in the light of the reports of the British secret agent Professor Ármin Vámbéry 2 was based on the documents first published in the Vámbéry biography of the British authors Alder and Dalby. 3 On the basis of Vámbéry’s letters preserved in the archives of the British Foreign Office, the Turkish author tried to present the Hungarian Turcologist as a spy and a double agent, and in the enlarged second edition of the book even his Jewish origin and his relations with the Zionist movement were highlighted. 4 Nevertheless, one can state that the merits of the Hungarian scholar have not yet been forgotten in Turkey, and still many books and conferences commemorate the adventurous traveler, who entered his name into the history of the Turkish, British and Hungarian people.